The Ten-Year Plan: what does it mean, what’s missing and what’s next?

The government’s Ten-Year Plan for the NHS in England has met with enthusiasm and exasperation in equal measure. We asked seven healthcare experts to give us their considered view on one aspect that interests, excites or annoys them.

Geoff Underwood, chair of MiP’s National Committee, on Strategic Commissioning

Dr Andy Brooks, National Association of Primary Care, on GPs

Lucina Rolewicz, Nuffield Trust, on Workforce

Jessica Morley, Yale University, on Tech

Nigel Edwards, healthcare policy advisor, on Neighbourhoods

Siva Anandaciva, King’s Fund, on Trusts

Andi Orlowski, Health Economics Unit, on Value

The NHS’s AI ‘revolution’: promise or peril?

Jessica Morley, associate research scientist at the Digital Ethics Centre, Yale University

Technology was always going to feature strongly in the Ten-Year Plan. Back in September 2024, Wes Streeting outlined three big shifts as solutions to the NHS crisis: from hospital to community, from analogue to digital, and from sickness to prevention. While the digital shift was the most overtly tech-centric, it was clear that all three would rely heavily on digital, data and artificial intelligence (AI) and, unsurprisingly, the published plan uses these three terms 102, 106, and 79 times respectively.

According to the Plan, the NHS will be the most AI-enabled health system globally by 2035. AI will automate triage, act as a trusted assistant embedded in care pathways, liberate staff from bureaucracy, support radiology reporting, assess patients remotely, predict hospital flow, discover medicines, and act as companion, coach, and GP via the NHS app. This will, ministers claim, give joy back to clinical staff, automate over a million administrative requests, and save 90 seconds per GP appointment—additional capacity equivalent to more than 2,000 full-time GPs.

While investing in life-saving technology is laudable, expectations are so high that the NHS risks putting far too many eggs in a relatively flimsy basket.

First, the plan perpetuates myths about NHS having “the best population health data in the world”. In reality, NHS data assets are often siloed and rarely AI-ready, requiring standardised curation and careful interpretation by specialists. The 5.6% opt-out rate also undermines completeness and risks bias.

Second, prediction doesn’t equal prevention. The Plan’s faith in genomics and predictive analytics ignores substantial evidence of their limitations. The predictive power of genomics is often modest; relying too heavily on predictions based on polygenic risk scores can be counterproductive, and widen rather than narrow health inequalities. And population risk stratification tools rarely produce benefits—in fact, they can make care worse, especially for marginalised patient groups.

Third, evidence for effective AI-enabled hospital care is currently weak. The Plan cherry-picks examples while ignoring systematic evidence that AI’s real-world performance is often poor. Multiple systematic reviews demonstrate weak evidence of effectiveness, small effect sizes, non-transparent reporting and significant implementation challenges.

Fourth, ambient AI scribes pose safety concerns and should not be blindly trusted. These systems are stochastic inference machines making active ‘decisions’ about clinical relevance based on biased and incomplete data. They can generate different results each time, potentially even for identical consultations with the same patient. And we have limited control over data flows and background processing, raising significant privacy concerns.

Fifth, over-reliance on AI risks widening inequalities. The Plan promises to help those “who have not previously been able to access healthcare on their own terms,” but AI systems are likely to perform worst for populations with the greatest health needs. This reflects systematic biases throughout the development pipeline, from dataset composition to algorithm design. Those who generate high-quality data about themselves (the ‘worried well’) benefit most, while those with greatest health needs are left behind.

Finally, the plan underestimates implementation complexity. Brief nods to reviewing regulations feel like afterthoughts. Successful AI implementation requires robust infrastructure spanning technical, social, ethical, and regulatory domains, privacy-preserving mechanisms, curated datasets, interoperability standards, and designs that support clinical expertise.

The NHS has repeatedly failed to deliver similar digital promises. Without addressing fundamental challenges, the Plan risks repeating historical mistakes with newer technology.

Are ICBs being set up to fail?

Geoff Underwood, chair of MiP’s National Committee and programme director at South Central and West Commissioning Support Unit

After considerable time spent, coffee consumed and steps counted around the fields of north Somerset, while thinking about what the Ten-Year Plan says about strategic commissioning, here’s my view: the plan is a mess and it’s setting ICBs up to fail.

First, the mess, also known as Chapter 5 on the new operating model. It says ICBs will “draw on a deep understanding of population need,” and “deep engagement with patients and the public”. Health and Wellbeing Boards will produce neighbourhood health plans for ICBs to bring together “into a population health improvement plan for their footprint”. ICBs will then “be responsible for commissioning the best, most appropriate neighbourhood providers”. When something goes wrong, ICBs “will take decisive action to decommission services or terminate contracts where a provider consistently delivers very poor-quality care.”

But ICBs aren’t in sole charge. Regions will performance manage the providers commissioned by ICBs using “a rules-based process to determine where intervention and support to address poor-performance is needed… backed by a new failure regime”. (I think “failure regime” is a practically and morally wrong way to frame an improvement intervention in healthcare, but that’s an argument for another day). The plan continues: “Where we identify problems, we will then help solve them” by supporting reconfiguration of services, replacing leadership teams or placing failing providers into administration. I think “we” in this context means the Department.

To further muddy the waters, ICBs won’t be the only commissioners. The “very best” foundation trusts will become ‘integrated health organisations’. IHOs will, “hold the whole health budget for a local population” and “will be free to contract with other service providers, within and outside the NHS.”

It seems the ultimate goal for ICBs is to make themselves redundant by strategically commissioning local providers who regions and the Department approve of so much they become local commissioning providers who strategically commission other local providers locally.

But ICBs won’t be able to do that because I think they’re being set up to fail. They will “need to evolve new capabilities to be successful” but with half their previous resources. Most ICBs will cover much larger populations than now—the largest will serve over 3.2 million people, roughly the population of Uruguay. Full disclosure: I haven’t been there. But there must be a lot of neighbourhoods in Uruguay.

ICBs will not have the resources to analyse or engage with neighbourhoods in any “deep” way. I understand the emerging intention is that ICB staff who lead on neighbourhood development won’t follow their colleagues through the 50% grinder to the new ICBs, but transfer out to providers. So ICBs may not even employ the people whose job it is to have the deep understanding of neighbourhoods that ICBs are supposed to have.

This won’t be the end of the turmoil for ICBs. The plan encourages them to “adjust their boundaries” to be coterminous with strategic local authorities. As one ICB executive said to me recently, “It’s bonkers, we’ll be doing all this again in two years.” ICBs may not even have time to fail before they get reorganised again.

We had 42 commissioning organisations with detailed integrated care strategies and joint forward plans ready to go. We didn’t need to do this.

Impatience is a big threat to neighbourhood NHS plans

Nigel Edwards, senior policy adviser at PPL consultants and former chief executive of the Nuffield Trust

Perhaps the most significant idea in the Ten-Year Plan’s long list of proposals is the development of the neighbourhood health concept. This builds on work already underway following Dr Clare Fuller’s 2022 ‘stocktake’ on integrating primary care.

There will be a national development programme in which 42 ‘places’ will be supported to push the idea forward. However, other places will not want to wait—and nor should they, as developing this type of model takes time and some aspects of the process cannot be easily leap-frogged. The Plan says little about how change will be made but previous experience suggests that policy-makers underestimate the time and effort required to achieve it.

A lot of work is needed to develop the systems that will underpin these models. Some community staff will need to be realigned to work in neighbourhoods. Work on getting information systems aligned and talking to each other will need to be accelerated. I’m concerned that that GP practices are not as central as evidence suggests they should be—ensuring that general practice is strong, resilient, and able to adopt new pathways and work more collectively will be very important. While there are advantages to a scaled-up approach to primary care, relational continuity will still be important for a significant proportion of patients. Finding ways to get the best of both will be a challenge, but methods do exist, such as ‘microteams’ with their own patient list working as part of larger practices.

Acute trusts need to think about how referral systems work and develop new ways for specialists to support GPs. Models to do this are already in place in some areas; they involve replacing some referrals with advice and guidance, having util-disciplinary review meetings between neighbourhood teams and consultants, and streamlining communication to reduce the number of tasks hospitals hand to GPs. This will mean creating new job plans and pathways to support these new approaches. This work will also help to realise the Plan’s goals for reducing use of outpatients and, experience suggests, reduce admissions for chronic conditions.

Experience also suggests this sort of integration needs to be organised and co-ordinated. There will be difficult decisions about resource allocation because, as teams are formed, we will find that the inverse care law—that the availability of good medical care varies inversely with the need for it—is still very much in force. The development of an ‘integrator’ function alongside a new model of commissioning will be important to drive change locally. The NHS has tended to ask commissioners to specify far too much detail about what is provided, and the model will need adapt to a more outcome-based approach as systems become more integrated.

There is an important lesson that the Plan does not seem to have learned from previous experience: the development of integrated services and teams cannot be mandated. While systems and processes can be put in place, success depends as much on relationships and staff aligning to a different set of objectives and success criteria. This takes time, effort and resources. Impatience about this is one of the biggest risks facing the Plan— and only local leaders can manage it.

It’s hard to be optimistic with misty optics

Dr Andy Brooks, GP and chair elect of the National Association of Primary Care

How has the Ten-Year Plan landed with you? Are you eager for change or thinking, here we go again? How we view the Plan may depend on what lens we’re looking through—our experience and position always colour and sometimes cloud our perspective. There are some optimists chomping at the bit to get started, and some who can’t even find a glass, never mind whether it’s half-full or half-empty.

While there isn’t much detail, general practice is at the heart of plans for neighbourhood health services. The vision is for a fundamental shift away from a hospital-dominated system, delivering more care in the community by focusing on long-term relational care, increasing capacity in primary care and investing in estates, digital and workforce. Surely, all this is good news for general practice?

However, reaction in the world of general practice has been mixed. Some say “don’t touch it with a bargepole” while others advocate jumping in and shaping the plans—through the recently launched neighbourhood health implementation programme, for example. Why are some in general practice optimistic while others seem to have misty optics?

One of the big concerns is the proposal for two new contracts: one for neighbourhoods with populations of 50,000 and one for multi-neighbourhood providers serving populations of 250,000. Immediately, questions arise about what they mean for standard GP contracts, primary care network (PCN) contracts, GP federations, and what some see as the threat from trusts becoming integrated health organisations (IHOs).

These are significant concerns, especially when combined with current underspends in primary care budgets, including those for transformation, enhanced services and workforce. History tells us that investment tends to shift right, not left. Many NHS providers and commissioners are in deficit, but the one sector that isn’t is general practice. It simply can’t be: deficits become a personal financial loss for GPs as business owners. No wonder so many in general practice are looking at the Plan through misty lenses. Their concerns must be acknowledged—simply suggesting that they need new specs isn’t going to help.

I’m at heart an optimist who likes to embrace challenge and change. I’ve found that getting involved and being part of the conversation leads to better general practice, better system working and better outcomes for the public. But I’ve also learned that there are often nuggets to be found by listening to those with a different perspective, those who are cautious, point out risks and understand the complexities of care. Taking time to understand and mitigate concerns without losing sight of the vision or the necessary momentum is a skill of competent leadership.

Ultimately, whether our optics are clear or clouded, the challenge before us is the same: to move from vision to reality in a way that strengthens general practice and builds healthier neighbourhoods. Optimism alone will not deliver change, nor will caution prevent it—what matters is how we balance both, working together with honesty about the risks and determination about the opportunities. If we can find that balance, the aspirational words in the Ten-Year Plan may become a lived experience of better, more connected care for the communities we serve.

Foundation trusts were the future, once

Siva Anandaciva, director of policy, events and partnerships at the King’s Fund

There are some old ideas in the government’s new Ten-Year Plan. One of the oldest (and most technocratic) is the promise of a “reinvigorated” foundation trust model.

Foundation trusts (FTs) were legally different from their NHS trust predecessors. FTs were meant to be quasi-autonomous NHS organisations, freer from central oversight and regulation, and more accountable to local communities.

Some things did feel different. I saw CEOs of first-wave FTs who no longer had to wait for Whitehall’s approval for strategic decisions, and FTs using their commercial freedoms to set up subsidiary companies or—rarely—deviate from national frameworks like Agenda for Change.

But there were limits. Most FTs still relied on government revenue and had to meet the same performance standards as everyone else. Having two types of trust was a real headache for national NHS leaders, who had to withhold investment from NHS trusts in case FTs decided to spend their reserves and blow the overall NHS budget.

And it was never clear that FTs were ‘better’ than trusts. They didn’t perform significantly better on finances, patient satisfaction or waiting times. Which led some government advisors to privately muse, “Well what’s the [bleeping] point of them then?”

That hasn’t stopped ministers resurrecting the idea. The Plan says the first ‘new’ FTs will be authorised in 2026, with every provider becoming one by 2035. And the ‘very best’ FTs will be eligible to hold population-wide budgets and become proto-integrated health organisations (IHOs) by 2027. Without a detailed implementation plan, it’s impossible to know how IHOs will work with existing providers or ICBs, or why FT freedoms are essential to being an IHO. But we do know that FT status is now a necessary first step towards becoming a nationally-recognised IHO.

The FT resurrection poses interesting policy questions. The new model jettisons some elements of local accountability, like the need for governors, without an obvious replacement. And it’s still unclear how FTs can use their commercial freedoms when every spending decision will score against the government’s balance sheet.

Perhaps most interesting is what this says about the beliefs of national policy-makers. Much of the senior leadership of both the Department of Health and Social Care and NHS England were either architects of the foundation trust policy over 20 years ago or have run foundation trusts. They found you could do more, and do it faster, to improve patient care if high-performing organisations were unleashed, with less bureaucracy holding them back.

That may be the biggest problem in some parts of the NHS, but it’s surely not the case across the board. So, there’s a real danger that this policy is about letting the best parts of the NHS race away, rather than letting the most challenged parts catch-up.

I was in the Department when FTs were all the rage, I worked for the Foundation Trust Network [now NHS Providers] and I’ve been an FT governor. I genuinely believe the FT ‘movement’ worked in some ways, and that the entire NHS cannot be run directly from Whitehall. But I’m still sceptical that FT status is the answer to the problems the NHS faces. As my neon socks demonstrate, if you wait long enough, everything comes back into fashion. But as those socks also show, sometimes you should think twice before bringing things back from the past.

Investing in NHS staff will be crucial

Lucina Rolewicz, workforce researcher at the Nuffield Trust

The 2023 NHS Workforce Plan was the first large-scale, long-term workforce modelling exercise for the NHS. It was criticised for having unrealistic expectations of workforce growth and questionable modelling assumptions. The Ten-Year Plan rejected the 2023 plan as “a fiction”, but there is hope that a new workforce plan due this autumn will remedy its failures.

The Ten-Year Plan’s vision for three big shifts in care—from hospital to community, analogue to digital, and sickness to prevention—will have big implications for where and how staff train and work.

The main workforce ambitions in the Plan are:

- Growing a sustainable, domestic supply of NHS staff. Reducing reliance on international recruitment developing more talent from local communities is no small challenge. The latest available data show more than two-thirds of new doctors and almost half of new nurses were trained overseas.

- Making the NHS an employer of choice. This means tackling structural issues and smaller, everyday frustrations. Small wins will include an NHS staff app to make HR processes more accessible and reforming mandatory training requirements. Better support for staff returning from long-term sickness absence is also crucial, as such staff are more likely to leave their jobs.

- Equipping staff for a digitally enabled NHS. Lack of career progression is a longstanding factor in NHS staff turnover. The plan’s proposed “skills escalators” aim to give staff personalised career development and clear advancement routes—including training in using digital and AI tools, which are expected to play a big role in reducing administrative burdens.

To create a domestic training pipeline fit for the future, clinical careers must be attractive, and universities and employers need to reduce attrition during training and encourage participation in healthcare careers. The Nuffield Trust has previously recommended student loans forgiveness or similar policies to incentivise students to choose NHS careers and reduce early-career leavers.

The recent announcement of job guarantees for new nursing and midwifery graduates is encouraging, but some of the practicalities remain unclear—including how trusts and universities will determine where staff are most needed, and how this squares with the wider aim of shifting care—and therefore jobs—into the community. Retaining higher apprenticeship funding for key community roles (such as district nurses) is welcome too, as these jobs are essential to the shift.

But these recruitment efforts will fall flat if the NHS can’t retain staff for the long term. The NHS needs better information on why staff leave and where they go next, and to identify staff who are most likely to leave and target interventions accordingly.

Digital and AI skills will be important, but the NHS needs to be able to walk before it can run. Prioritising upgrades to basic IT systems, introducing fully integrated digital patient records, and establishing adequate data infrastructures are essential to integrate existing processes with new digital solutions.

If the NHS can nurture more homegrown talent, retain staff and equip them for a digital-first service, it will take important steps towards its long-term ambitions. But our studies of other countries, like Denmark and Ireland, have demonstrated that additional investment, contractual changes, and financial incentives are needed to make some of these big changes a reality.

Back to school for the NHS

Andi Orlowski, director of the NHS Health Economics Unit

Picture this. You’re getting Timmy ready for school. New pencil case, shiny shoes and creaseless shirt. But meanwhile the school has been preparing for months. Timetables set. Staff lined up. Classrooms ready. Day one works because preparation is real, practical and focused.

The NHS Ten-Year Plan is that same preparation for our health service. It’s the curriculum, the timetable and the room plan, all organised around ‘value’. The NHS won’t deliver better outcomes for every pound without deliberate choices about what to stop, start and scale.

Here’s the curriculum—what the Plan says about value:

- Finance built around value: Move away from paying for volume. Use best practice prices, test Year of Care payments and reward high quality and patient experience. Over time, providers are rewarded for improving outcomes, not just activity.

- Shift spending to where it works: Reduce the share of spending in hospitals and invest more in primary and community services, aligned to need and delivered through neighbourhood teams.

- Productivity and discipline: Better health for the same staff time, theatres and kit, with outcomes and patient experience protected. If quality slips, productivity falls.

- Transparency and low-value care: Publish outcomes and access by place, increase use of patient outcome and experience measures, and decommission low-value activity. Strengthen NICE to identify what adds little benefit.

- Capital and estates to enable the shift: Progress Neighbourhood Health Centres and consider partnership models to move services closer to home.

- Earned autonomy and clear roles: High performers gain more freedom to innovate, alongside a tougher improvement regime where quality lags. ICBs focus on strategy and outcomes, with providers more accountable for population health delivery.

Delivering the curriculum demands analytics, clinical leadership and honest public conversation.

- Set your value syllabus. Pick three conditions and two cross-cutting aims. For each, agree the outcomes that matter, including equity and experience. Map the payment lever you will use: best practice price, blended payment or a Year of Care bundle?

- Work on allocative efficiency. Bring clinicians, finance, analysts and public voice into one room. Score options against outcomes, equity, affordability and feasibility. Decide what to stop, start and scale. Publish the criteria, weights and rationale. (Use STAR or PBMA — they’re free!).

- Pilot Year of Care. Start with long-term conditions where integrated teams already exist. Write one simple bundled-payment spec, one outcome dashboard, and one gain-share rule with providers. Build in patient feedback and case-mix adjusters.

- Create a reinvestment pipeline. Commit to removing at least one line of low-value activity this year. Move that money to an evidence-based community offer. Track both the pounds and the benefits.

- Wire up the analytics. Build a clean, reproducible pipeline for activity, cost and outcomes. Give boards a single page showing outcomes, experience, equity and spend, and use tools like Model Health System and GIRFT to reduce unwarranted variation. Professionalise the analyst workforce so decision-grade work is the norm.

- Make transparency about improvement, not blame. Talk about published place-based results with staff and communities. Celebrate outliers who improve outcomes, and support teams that need to catch up.

Back to school energy matters. The Plan gives us the curriculum. If we choose well, measure what matters, move resources and support teams, patients will feel the difference. Better outcomes. Better experience. Better equity. That is the job… and no sausages thrown in the canteen!

Related Stories

-

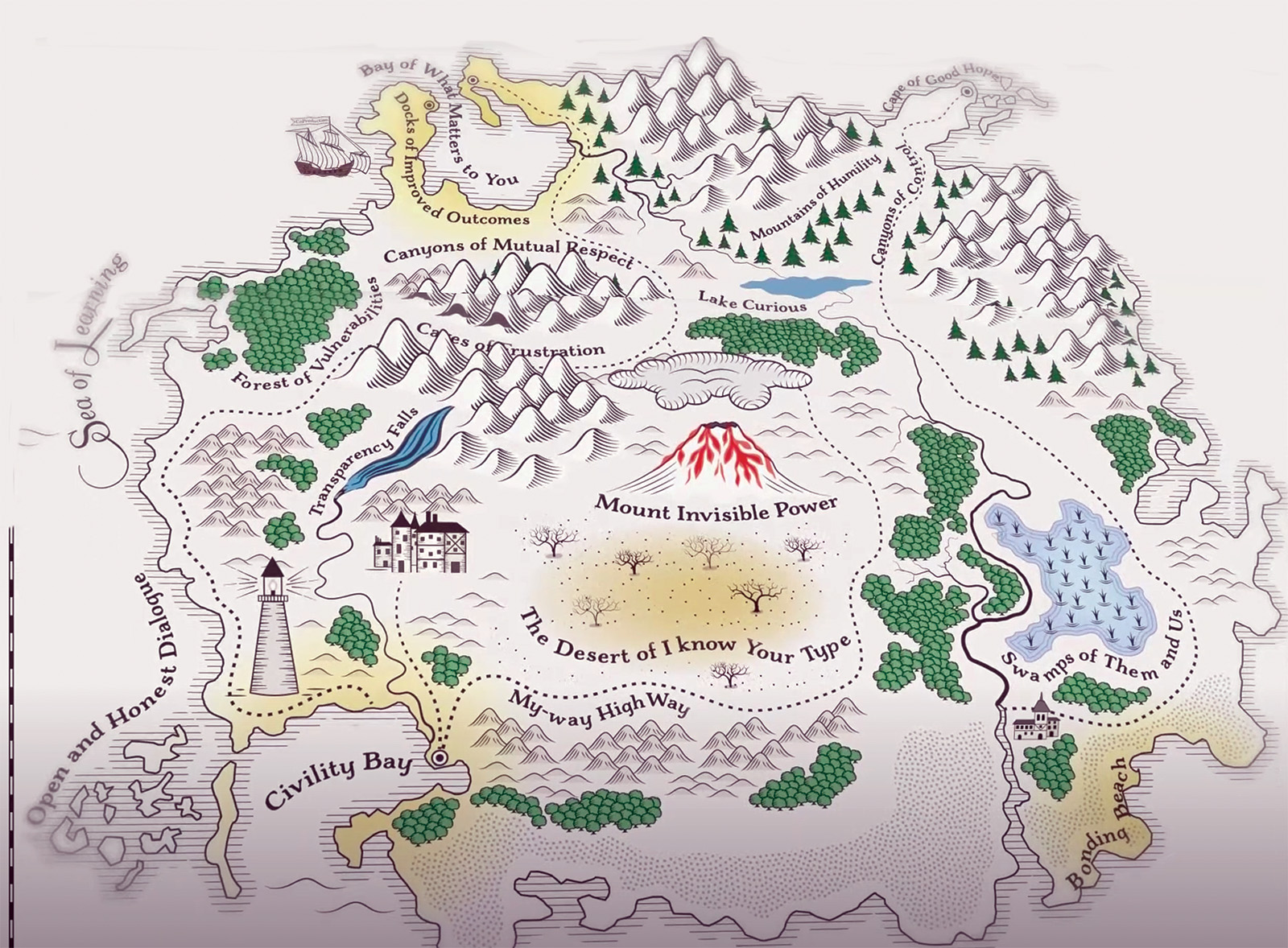

Co-production: say it like you mean it

The NHS talks a good game on co-production, but many patients and carers still feel service changes are done ‘to’ them not ‘with’ them. As Jessica Bradley discovers, meaningful co-production means building lasting relationships and sharing decision making power.

-

Holyrood elections: Back from the brink—for more of the same?

After a big scare last year, the SNP are now clear favourites to extend their rule at Holyrood into a third decade, pointing to incremental reform rather than radical change for the NHS in Scotland. Rhys McKenzie reports.

-

Senedd elections: Tough choices, empty promises

As we enter 2026, the NHS in Wales faces some stark choices and a likely change of government. But the parties vying for power at Cardiff Bay will need to up their game to meet the challenges ahead. Craig Ryan reports.

Latest News

-

Government proposal for sub-inflation pay rise “not good enough”, says MiP

Pay rises for most NHS staff should be restricted to an “affordable” 2.5% next year to deliver improvements to NHS services and avoid “difficult” trade-offs, the UK government has said.

-

Unions refuse to back “grossly unfair” voluntary exit scheme for ICB and NHS England staff

NHS trade unions, including MiP, have refused to endorse NHS England’s national voluntary redundancy (VR) scheme, describing some aspects of the scheme as “grossly unfair” and warning of “potentially serious” tax implications.

-

Urgent action needed retain and recruit senior leaders, says MiP

NHS leaders are experiencing more work-related stress and lower morale, with the government’s sweeping reforms of the NHS in England a major factor, according to a new MiP survey.