Tough choices, empty promises

As we enter 2026, the NHS in Wales faces some stark choices and a likely change of government. But the parties vying for power at Cardiff Bay will need to up their game to meet the challenges ahead. Craig Ryan reports.

The NHS in Wales, like the country itself, is at a crossroads. It’s almost certain that the Senedd elections on 7 May will see the first change of government since devolution in 1999. Leading the polls are Plaid Cymru and Reform UK, two parties united only by their fierce criticism of how Labour—languishing in a distant third—has run the NHS. In Wales, the NHS really matters, and all parties are desperate to convince voters they can do something to fix it.

The NHS in Wales is struggling. One in six people are on an NHS waiting list, and 10,000 have been waiting for more than two years. On cancer treatment, A&E and ambulance responses, performance is way off target. And health inequality is rampant: in the South Wales valleys, 11% of adults are in poor health and life expectancy can be 12 years shorter than in Wales’s most prosperous communities.

All familiar problems, but they feel particularly acute and immediate in Wales. A new government could be a chance to try something different.

‘We can’t keep throwing money’

“We can’t keep throwing money—that’s not the solution,” says Helen Howson, director of the Bevan Commission, Wales’s leading independent healthcare think tank. “We need to talk about a sustainable workforce, sustainable services and sustainable systems. We have to get our heads around that.”

Not that there’s much money to throw. Since 1999, spending on health and care has risen from 34% to 49% of the Welsh government’s budget—and there’s little to no chance of Westminster coughing up any more cash, despite Wales’s undoubted needs. So, the key question, says Howson, is: “How do we build financial sustainability into a system that’s going to have even greater demands on it in the future?”

State-funded healthcare systems are under demographic and economic pressure everywhere, but Wales is at the sharp end. “We’re a sicker, more deprived nation with an older population as well,” explains Nesta Lloyd Jones, deputy director of the NHS Confederation Wales, with an obvious “impact on the number of people accessing services or on waiting lists”.

Howson says this “ball and chain that’s been hung on us” means the next government in Cardiff Bay will have to show “bold, courageous leadership” and take “a really hard look at how we’re using the resources we already have”.

Research by the Bevan Commission found 20% to 30% “waste in the system”—but those savings won’t be achieved by cutting management jobs, as some Reform politicians have claimed. Beyond some low-hanging fruit like temporary staff, streamlining administration and energy consumption, the big money will come from shifting the NHS towards prevention and “co-producing health locally with people”, Howson explains.

“Are current services doing the right thing to the right people at the right time, in the right way? Are we over-treating? Are we doing things we don’t need to?” she says.

She gives the example of a hand surgeon—one of the Commission’s 800 ‘exemplars’ of good practice—who developed a non-surgical treatment for Carpal Tunnel, slashing staff costs and treatment times and freeing up theatre capacity. “If you can do it with hands, you can do it with feet, surely?” says Howson. Encouraging and spreading these “great ways of thinking… can’t be directed from the top down,” she adds.

Marmot nation

Looking to up Labour’s game, health secretary Jeremy Miles announced in June that Wales would become a ‘Marmot nation’— putting into practice the thinking of Professor Sir Michael Marmot: in short, that the key to better population health and sustainable health services is integration—not just health and care but all services and policies affecting health, including housing education, poverty reduction and discrimination.

Wales already has integrated health and care boards but “the priority is still on the acutes”, explains Lloyd Jones. The Confed has called for a new performance and financial framework that moves the goalposts towards health outcomes rather than traditional activity measures. “Unless we shift the priorities… into community and preventative measures, the money will still go where the spotlight is.”

An experiment with ‘joint outcome frameworks’ in the Cardiff area shows how this might work. Local councils and the health board pool their budgets and work together to get the best outcome for each patient—which might be care at home rather than more expensive hospital treatment. “Having these joint frameworks means the money shouldn’t be a barrier,” Lloyd Jones says.

At the crossroads

This long-term stuff hasn’t featured much in campaigning, with opposition parties naturally focusing on waiting lists, and making the usual promises to recruit more doctors and nurses. So far, neither Plaid nor Reform have gone much beyond pointing to problems and promising, vaguely but vociferously, to fix them.

Plaid has at least published some proposals, promising to cut waiting lists with temporary ‘surgical hubs’ and a new ‘executive triage service’, as well as ‘using technology’ to speed up diagnoses and improving collaboration between Wales’s seven health boards. Health spokesperson Mabon ap Gwynfor says the plan “shows we are serious about fixing the NHS”, but the details remain sketchy with no indication of how the schemes would be staffed or funded.

Plaid is keen to burnish its prevention credentials, with leader Rhun ap Iorwerth recently pledging to boost prevention spending and put a public health minister in the cabinet. The party also wants to end the “artificial” distinction between health and social care with a new ‘national care service’, despite Scotland scrapping a similar scheme earlier this year.

The dilemma remains that, in a resource-constrained system, investing in prevention means taking money way from hospitals and other ‘visible’ NHS services, something politicians talk about but rarely do. How will Plaid resolve that? We still have no idea.

Reform UK—leading in some recent polls—has been left scrambling to catch up. Healthcare Manager understands that, this autumn, party officials wrote to Welsh healthcare organisations asking for 500-word summary of their priorities. In October, Nigel Farage told the BBC that the party has a “full-time team” working on policies that would bring “fresh thinking” to the NHS in Wales. “We’re taking this very, very seriously indeed… but it’s too early to give answers to all of these things,” he said.

Laura Anne Jones, Reform’s only member of the Senedd, has worked hard to distance the party in Wales from Farage’s repeated musings about scrapping the NHS funding model, insisting that Reform would keep the NHS “free at the point of use”. Both Jones and deputy leader Richard Tice have claimed that the Welsh NHS doesn’t need more money, just fewer managers.

Reform would “cut wasteful bureaucracy and unnecessary management, putting clinicians back in charge. This alone frees millions to invest in frontline care without extra taxes, ensuring prescriptions remain free,” Jones told the Senedd in September.

Reform’s manifesto for last year’s general election did sketch out some eye-catching policies, including running operating theatres at weekends, tax breaks for NHS staff, vouchers for private care to clear waiting lists and a public inquiry into “vaccine harms”. It’s unclear whether any of these pledges would apply in Wales.

Under Wales’s new electoral system, no party will get near a majority in May, and Plaid is more likely than Reform to be able to form a stable coalition. Whoever wins, parties will have to forge some sort of consensus on the future of the NHS in Wales.

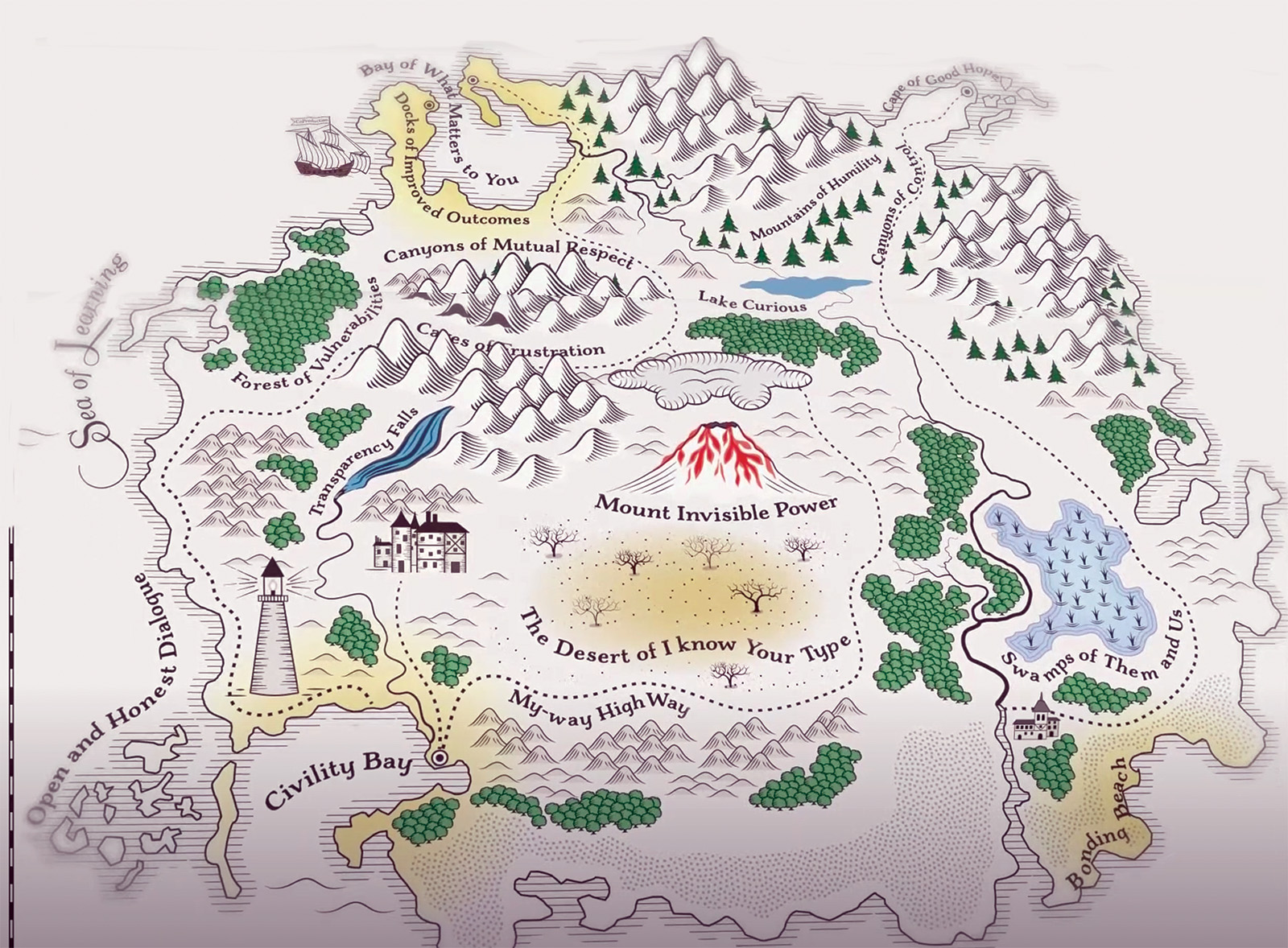

The long-term investment and change the NHS needs won’t be delivered by another auction of meaningless promises. Instead, politicians need build a new partnership, not just with each other, but with councils, community groups, national NHS leaders and local managers. If they can do that, maybe NHS Wales become a beacon for how state-run healthcare can transform itself for the modern age.

But at any crossroads there are three possible paths, not two: carrying on, pretending we can do everything, ignoring the trade offs and hoping for the best, is always an option— it’s a path well-trodden in the past. But Wales’s next government may quickly find that path is blocked not very far ahead. //

Related Stories

-

Co-production: say it like you mean it

The NHS talks a good game on co-production, but many patients and carers still feel service changes are done ‘to’ them not ‘with’ them. As Jessica Bradley discovers, meaningful co-production means building lasting relationships and sharing decision making power.

-

Holyrood elections: Back from the brink—for more of the same?

After a big scare last year, the SNP are now clear favourites to extend their rule at Holyrood into a third decade, pointing to incremental reform rather than radical change for the NHS in Scotland. Rhys McKenzie reports.

-

NHS job cuts: you’ll never walk alone

As the NHS redundancies in England loom, Rhys McKenzie explains how MiP will back you, and how members supporting each other and acting collectively is the best way to navigate this difficult process.

Latest News

-

Job vacancy: MiP Assistant National Organiser

MiP is looking to recruit an Assistant National Organiser on a 14 month fixed term contract. Applications close: 4 March 2026.

-

FDA General Secretary Election 2026

Please find important information regarding the FDA General Secretary Election 2026 which MiP members may participate in.

-

Government proposal for sub-inflation pay rise “not good enough”, says MiP

Pay rises for most NHS staff should be restricted to an “affordable” 2.5% next year to deliver improvements to NHS services and avoid “difficult” trade-offs, the UK government has said.